Hasta El Fin [Vasco + Emma]

Jul 18, 2018 0:09:34 GMT -5

Post by Deleted on Jul 18, 2018 0:09:34 GMT -5

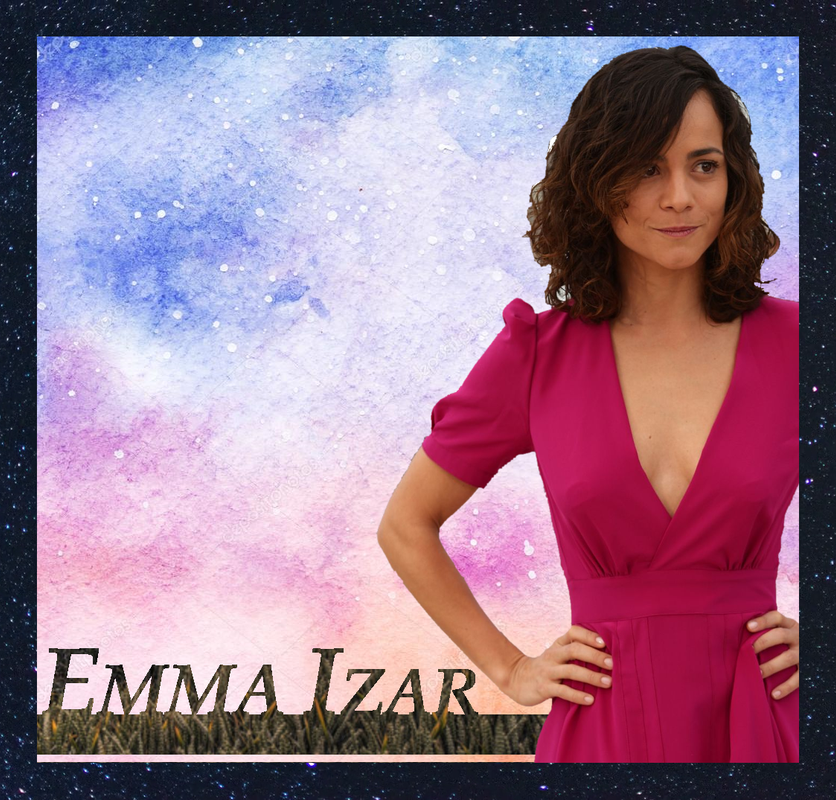

Vasco Izar

We have walked as though the world has not changed.

Gabriel is gone—another strong set of hands, a youthful smile, full of promise. He used to watch Yani when I needed to see my brothers, and Emma had work to be done in the house. I like to think he taught her how to count to three, with his dice (I told him she wasn’t supposed to know how to gamble until she was at least six, but—I don’t fault him for teaching the chance life has so young). I think about him a lot now, digging in the dirt of the summer, sweating through my shirt as I pry up stalks of corn, or potatoes. He complained a lot less than Emmanuel does. A good boy, another one snuffed out like a candle burned too low. Que lástima, Marisol had said, Pero al mal tiempo, buena cara. She still wore black, even in the hundred degree heat, to mourn for him.

Why do we let ourselves get buried? I guess it’s just the human condition to feel a great weight from what we can’t control. The symbolism of life being taken over by this earth, the return, all of that makes it easier to let go. We’re supposed to let go, to let the waves rock us back and forth in our little boats, and then for the moment to pass. I have to be strong for them, to remember him, to remember Raquel, and Salome, and Benat, and Iago—(and Levi, I keep forgetting Levi)—but the heat mixes up their faces in my head every morning, so much that I don’t feel like talking to my brothers. Even Bakar tells me I’m too much like him lately, keeping to myself and staying out at odd hours. I say it’s Yani keeping me awake, which is half true. Another little one under three will put bags under anyone’s eyes.

But I sit on the porch most nights, staring up at the sky, and the stars. I let the humidity stick to my skin, and sweat drip down my shirtless chest to the old wooden porch. I sit, feet hanging over and off onto the ground, and stare out at the fields until I see shapes in the distance. Lightning bugs, darting here and there, guiding spirits through our farm. Do they come back to visit, I’ve wondered to myself, through the sleep in my eyes.

I only ever cry into my handkerchief, when I can hear the snores of Sofia and Emmanuel through the window. It’s going on three years since she died but—around this time every year I can’t help but shake it. It’s like a pit forms in my chest and swallows downward, endless into my heart and lungs, until I can feel all of it in my throat. And I know how beautiful she would be now, how she’d be old enough to settle down and start her own family. It kills another piece of me to think she’d have a child (she would’ve laughed and asked if I wanted to be an abuelo already but—I would’ve said yes, por dios ¡Claro que sí!). It’s not quite regret, but a longing that stick to your heart. An empty room with faded portraits and disappearing memories.

We’re stronger, I think—

The feeling will pass, if I have enough time. I gave away her things to the home and, I felt as though that was one weight lifted from my chest. But then, there was Gabriel, and… I suppose I wasn’t as far along as I thought. You think you’re stronger than you really are. In that moment, that if it was to happen again, that I’d face death and tell him there is nothing else he can take from me he hasn’t already. Except death laughs, because what he takes is not replaced or rebuilt, or a piece that can heal. I tell them she’s in a better place, but sometimes I wonder if she’s just in the ground in that cemetery. Just bones and skin and hair, that I did nothing but watch her lose her chance to be with us. A dead girl, tucked away in the corner of the world like the rest—so many children, all Izars, rotting at the edge of our district.

I’m sorry that I’m crying, because tonight was supposed to be happy.

The idea came when I was out on the porch, watching the sky. I wish I could say it was from a shooting star, or another sign from above but, it was just from the silence. We’d spent so many days setting one foot in front of another moving toward the end of a journey that didn’t exist for us. If I had to keep going like that, I’d surely die. And I thought that it had been so long since it was just us, together. I had started to forget the times that we lived for one another, and if there’s one thing I can’t abide it’s forgetting how you smile when you look at me, as though you’ve found something wonderful. And I think, how could you find something more wonderful than what I have?

I sent Emmanuel and Sofia away—they’d help Manuela with Izak and Amalia—and Marisol would take Yani. Her preciosa, as she liked to say.

So I set home before the sun sets, because Druso and Aresti have promised to cover in my absence. They caw like crows about my plan, but exact a just price for my request. For Druso, a month watching his children and teaching his boy to play the guitar. For Aresti, I’ve promised Emma’s jam, enough to last him through the winter, so long as he doesn’t get any fatter than he already is. They let out some gritos when I amble through the patchwork of cornstalks, and disappear into the field. The fibers of the leaves stick to my skin as I push through, head down. They bend as I swoop my arms through, heart beating with a quickness.

I am no miracle, no more special than any man that walks district eleven. I’m the shortest of my brothers and some of my nieces and nephews can already call me viejo. Simple and plain, but by god do I love my wife more than anything in this world.

Mi vida, ella es mi vida.

There is no secret like love—a phrase cliché enough for the young to roll there eyes, and laugh. But waking up in the morning underneath the covers, seeing her face next to mine is enough to drag these weary bones from my bed and press my feet against the floor. To see her smile when I pour the first cup of coffee helps the blood to flow through my veins. A kiss goodbye is air to my lungs, enough to know that between two bodies there exists a common heart. Even in the pain of what we’ve lost we’re still together—more wrinkles on our brows, aching backs, heavier hearts—but there is no one else that could be mine.

I can hear her coming up the walk when the sky has turned from red to mulberry. I’m tilted over a pot of carnitas adding a pinch more salt. She’ll step through the screen door at the porch and stretch her neck, and wonder, where have our children gone? Will she hear the music drifting through the air, reminding her of a night where we danced under stars and promised that no matter what our parents said, we’d stay together (I remember, I’ll always remember, Emma)? Te acompañará hasta el fin, I think.

“Mi vida,” I say, and step through to the sparse living room to wrap my arms around her. “Welcome home. And surprise…”